MAKING STEEL – A VERY CHALLENGING OCCUPATION.

By SYDNEY S. SLAVEN.

Working at a steel mill is among the most challenging occupations in the world. At a steel mill numerous occupational hazards come together such as molten metal, poisonous gas, moving equipment, overhead cranes, conveyor systems, high voltage and noise pollution.

The workers at the Sydney Steel Plant did not escape occupational hazards. The Memorial Monument at the United Steel-Workers of America Building in Sydney, N.S. is a testament to work place injury. The monument displays the names of over three hundred employees who lost their lives during the Sydney Steel Plant’s century of operation. One hundred and sixty-seven died in the years 1900 to 1920 alone. At that time, safety was a low priority.

In reality the number of deaths was much higher then what is recorded on the monument. Under the Disco regime a death had to occur on the plant property before is officially recognized. So, if an employee died off plant property from an injury incurred on site, it was not officially recognized as a steel plant fatality.

Before 1949 Newfoundland was a colony of the British Empire, and not part of Canada. Many Newfoundlanders came to Sydney to work at the Sydney Steel Plant during its construction, and later its operation. Some of the workers had official status, but the majority were illegal immigrants. These workers were encouraged by agents of Disco, to jump aboard the ore boats traveling from Belle Island, NFLD, to Sydney to meet the demand for labour. The workers were paid the lowest wages and put on the most dangerous jobs. The impact of the death of Newfoundland workers was minimal. No records of these deaths were made because officially these wrokers did not exist!

Another group of people that did not make it to the official accidental death list were the Black workers. Many experienced black steelworkers were recruited from the steel mills of Alabama and were to provide the steel making skills until the local workforce was trained and ready to take over. In 1905 four blacks were killed when a high voltage cable fell across the metal building they were in. Although the Halifax Evening Herald made note of it, their names are not on the official company casualty list. In 1901 the Halifax Evening Herald reported sixteen fatalities at the Sydney Plant. The Memorial Monument only lists six deaths, so it is likely the others causalities were Newfoundlanders and Black workers.

After 1901 the population of Sydney escalated from a couple of thousand to twenty thousand by 1920. It was realized that hospital facilities would have to be expanded to meet this increasing population, especially the number of injured steelworkers. The Brookland Hospital was sponsored by Disco and included a general men’s ward, a woman’s ward, and an eighteen-bed ward for steelworkers. The steel worker’s ward was almost always full. The Brookland Hospital operated from 1904 to 1919 when it was replaced by the first Sydney City Hospital.

In 1931 Dosco built a state of the art hospital on site. This included outpatient and inpatient services with a modern operating room and a six-bed ward. Also, there was always a doctor on duty and an in-residence nursing staff. The company soon realized there was a sharp reduction in lost time accidents and compensation fees. Safety conditions gradually improved at the Sydney Steel Plant. After the unionizing of its’ employees great strides in safety were taken. Co-operation with the union executive on safety became paramount.

Safety Challenges

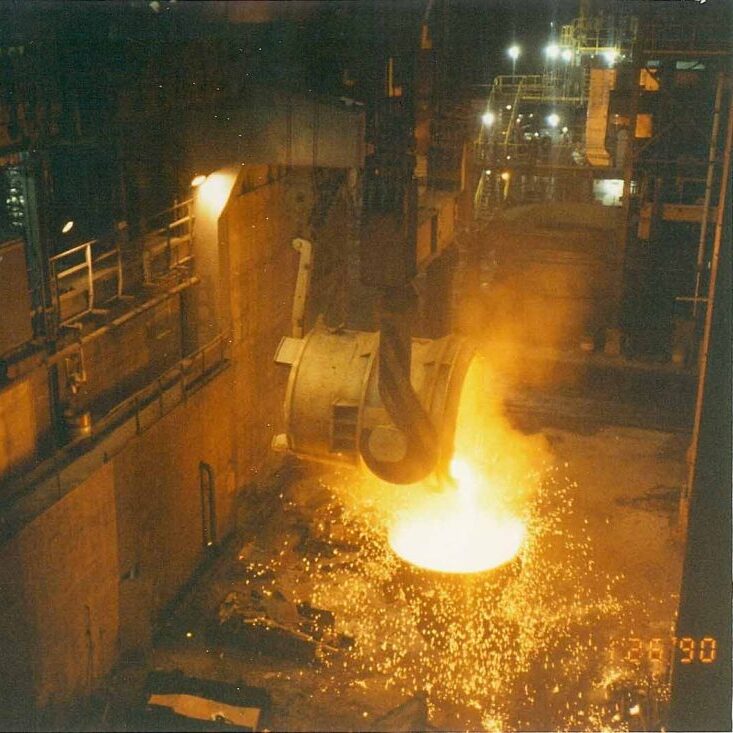

Iin the Open Hearth many elements of danger were present. Molten iron from the Blast Furnace was stored and poured on site. Steel was made in six tilting furnaces. The temperatures of these products were over two thousand degrees Fahrenheit. Also there were six overhead cranes traveling north to south, two at the front of the mill, and four at the back. Charging cars ran the length of the floor north to south. There were charging rams, which traveled east to west in and out of the furnaces. Cars of pans were shunted in and out of the mill and spotted in front of the furnaces. Locomotives ran up a trestle to the upper floor and up and down the length of the lower section. Add in noise, high voltage cables, poisonous gas, dust in the form of graphite, (a very slippery item underfoot), the explosion of a furnace being tapped, and many elements of industrial danger were present.

At on point in time, the nurses from the emergency hospital had never been on site. They saw the results of accidents, not the cause. When a gentleman named Romeo Sylvester was made Medical Supervisor he decided to remedy this and took the nurses on tour. They visited the Open Hearth. just as a furnace was being tapped. After they left one nurse remarked – ” My God, I’ve just been in hell.” Incidentally, there was a movie made in 1946, named “Angel On My Shoulder.” In it hell is depicted as being heated by an O.H. furnace were the dammed are sentenced to a lifetime of shoveling coal into the furnace. However, ask a plant worker it is a well-known fact that O.H. workers never go to hell. When they arrive before St. Peter at the Pearly Gates all they are required to state is – ” Another O.H. worker reporting sir. I’ve done my time in hell.” Admittance to heaven is instantly granted!

Other workers who died while serving the Steel Plant were the seamen who manned the ships. These ships transported iron ore from Newfoundland to Sydney during the Second World War. In the fall of 1942 four ships were sank by German Submarines at the Wabana site. The Steel Company owned one of these ships, while the other three were under charter. Seventy men died of which most were Cape Bretoners.

After the Steel Plant became a crown corporation in 1968 safety improved greatly and loss of life dropped to the lowest numbers in history. Strict safety requirements imposed by the Provincial Government aided in reducing the loss of life. In the past it was easy for private owners to ignore safety laws. The community feared the loss of employment – the well-known song was, “no smoke, no baloney.” Now as a Crown Corporation, the Provincial Safety Act had to be consciously followed. Provincial inspectors were often on site; they had the power to shut down anything they deemed unsafe.

One of these inspectors was the late George Scott who often said that there was no such thing as a safe steel plant, but it was our responsibility to make it as safe as possible.

There was camaraderie among steel-workers when it came to safety. They constantly looked out for each other. This was impressed upon all new employees. Veteran workers took newcomers under their wing until they were experienced enough to go on their own. A steelworker’s life depended on their fellow workers. Perhaps this was the most important safety program of them all – it saved many lives.