The Birth of a Steel Plant

By Sydney S. Slaven

The 20th century marked the rise and fall of a major steel industry in Sydney, N.S.

A small government town was transformed into a large industrial city that became known as “the steel capital of Eastern Canada”.

Today, bare acres and a few buildings are all that remain of the steel plant. The demise of the steel mill was due to several factor. The main factor was the reliance on only one product – the steel rail. Another factor was the disappearance of the third world market that began producing their own steel. Also, the North American Free Trade Act affected sales to Mexico. At one time, Sydney supplied all the rail needs of Mexico. It became cheaper for Mexico to produce its own rails due to the lower wages paid to its workers.

In 1899, an American businessman and promoter named Henry M. Whitney formed a consortium with the intention of constructing an integrated steel plant at Sydney, N.S. Mr. Whitney was well known as an astute businessman who, in fact, had once been a chief advisor to the President of the United States. He had already formed the Dominion Coal Company in 1893 and envisioned a local steel plant as the ideal outlet for coal.

Another steel plant was constructed at the same time in Sydney Mines by the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company, (Scotia). Mr. Whitney negotiated a deal to share the Wabana iron ore mine at Newfoundland with Scotia and named the Sydney operation the Dominion Iron and Steel Co. (DISCO). Limestone was also available in Aquatuna, Newfoundland. Consequently, all of the ingredients were on hand for the production of steel.

Sydney harbour also provided a shipping outlet to the world and to the Canadian National Railway, which terminated at Sydney and was a path to the central Canadian markets. The Scotia plant in Sydney Mines was a basic iron and steel producer feeding its finishing mills to New Glasgow, N.S. The Sydney plant was for the sale of semi-finished ingots, blooms and billets.

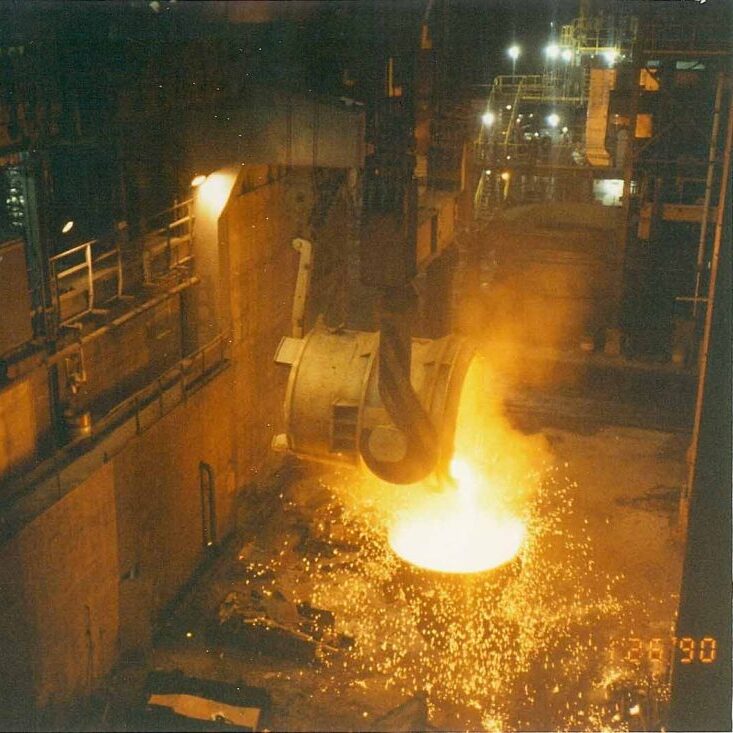

The construction of Disco began in 1900 and finished in late 1901. It was the most modern steel plant in the world with a state of the art battery of 400 Coke Ovens capable not only of producing coke, but also of recovering saleable by-products such as tar, benzene, and industrial salt. Four Blast Furnaces with a capacity of 1200 tons of iron fed off of themselves and used the heated gas produced to fuel further casts. Ten 50-ton Open Hearth furnaces of the tilting variety gave Disco the most advanced steel making process of the day.

Construction of the plant finished late in 1901 and the first steel was produced on Dec. 31, 1901(likely rushed in order to reach the target of a 1901 completion date). This was the beginning of 100 years of boom and bust cycles for the Sydney Steel Plant.

The downside of this modern plant was, the iron ore from Wabana and the coal from Cape Breton. The ore was of a very poor grade and the Cape Breton coal had extremely high sulfur content. For the next 60 years, removal of these impurities was a constant struggle for the steel makers. The mountain of slag adjacent to Muggah’s Creek is a testament to the amount of impurities removed over the years.

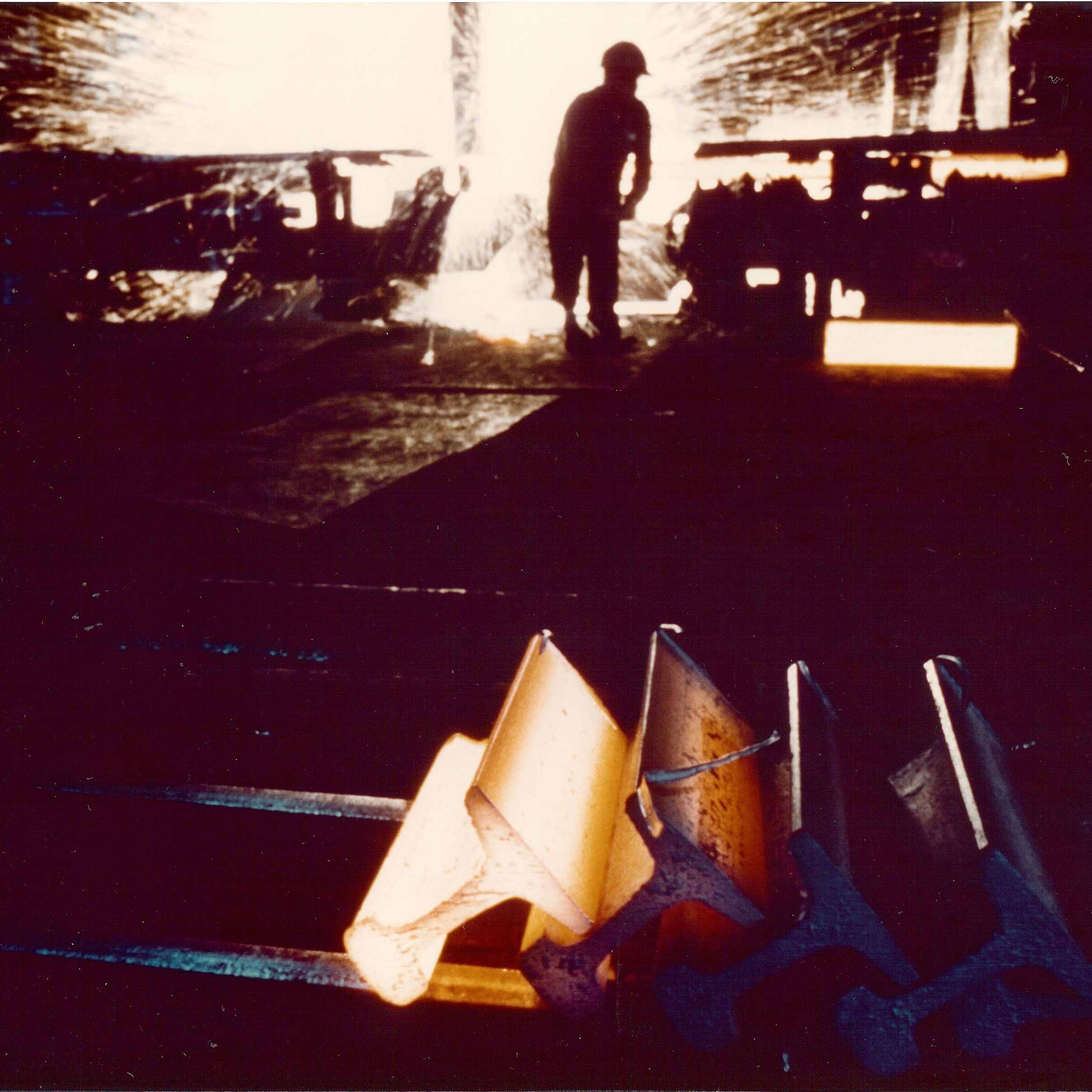

The Blooming Mill and Billet Mills were commissioned in 1902 and the sale of ingots, blooms and billets began. Although duties on imported steel were in place in Canada, it soon became apparent that Disco could not survive on the international sale of semi- finished products. Plans were made to diversify into other products such as rails, bars, rods, wire and nails. A Rail Mill opened in 1905 and rails became the chief product until the plant closed its doors in 2000. Two Bessemer converter furnaces were added in 1907 in an attempt to deal with the low grade iron ore and the high sulphur coal.

Disco had been a constant money loser up to this point but this situation improved when a domestic market developed for its rails. Whitney took this opportunity to promote the stock well above the book value and made a fortune when he sold out the steel and coal companies to a Canadian consortium in 1909. These two companies merged under the name Dominion Steel Company.

Disco floated a public bond issue to raise expansion capital and a new Blast Furnace came on stream in 1909. This was followed shortly by the commissioning of a Rod and Bar Mill as well as a Wire and Nail Mill in 1910. In the next two years, 4 Coke Ovens with 30 ovens each and another Blast Furnace were added. In 1913 another attempt to deal with steel impurities was made with the addition of two 500-ton mixing furnaces.

World War I (from 1914 – 1918) was a major boom cycle when the war effort took all of the steel that Disco could produce. A Plate Mill was constructed in 1918 but was mothballed because the war ended before it could begin operation. However, this mill would prove invaluable to the saving of Great Britain during World War II. More Coke Oven improvements were made in 1918 with the installation of two 60-oven batteries.

In 1920, a syndicate known as the British Empire Steel Corporation, (BESCO), acquired all assets of not only Disco, but Scotia as well. These included the mines at Wabana, the limestone operation at Aquatuna, Nfld., as well as the Halifax Shipyards. By now the steel industry was in a recession with the drop in demand, which accompanied the end of the war. Besco was badly undercapitalized and found itself in financial trouble from the start. Capital for modernization and expansion was not available and a number of money reducing routes were taken This led to a very violent period in the history of Cape Breton steel and coal.

The Scotia Plant at Sydney Mines was shut down and the works at New Glasgow were now to be fed from the Sydney works. Wages were cut and massive layoffs triggered violent strikes in the area. Besco formed a police force, (some would say a goon squad), to combat the strikers. The Canadian Military had to send in a large force of troops to act as peacekeepers between Besco and the workers. However, there was just not much demand for steel and, by 1927, Besco had collapsed into bankruptcy and went into receivership.

Strangely enough, the Sydney Plant prospered over the next two years because of government freight subsidies which allowed the plant to compete in the Central Canadian market. This short boom cycle attracted new investors and, in 1929, a British consortium took over the Besco operations and was called the Dominon Steel and Coal Company, (DOSCO).

Dosco inherited a disgruntled workforce and, in order to rectify this, introduced a concept that became known as “Welfare Capitalism”. This was implemented to meet some of the worker’s basic social welfare needs and, the main goal was a happy, contented worker. 1931 saw the completion of an on-site, completely integrated, modern hospital. It provided outpatient and in-patient treatment. There was a fully equipped operating room, a treatment room, a doctor on duty, an X-Ray room, a six-bed in-patient ward, and a live-in nursing staff. An ambulance was purchased for transportation of injured employees. From the start, lost time due to accidents was dramatically reduced and there were other side benefits as well. For example, hospital operations led to lower compensation costs while chest x-rays prevented the hiring of personnel suffering from tuberculosis. (Tuberculosis was a major illness of the first half of the 20th century).

Unfortunately, the 1930’s were another bust cycle with the Great Depression taking its toll at the Sydney Steel Plant. It took another world war for the plant to get back on its feet although a positive major event took place in 1931. This was the introduction of the Mackie Retarded Cooling Process. It was a method of controlled cooling of rails to rid them of hydrogen bubbles, (shatter), and had been invented by a Dosco metallurgist named I.C. Mackie. Dosco was now able to provide the world’s finest rail.

Another major event that occurred during this period was the formation of the first workers union in 1938 – Local 1064, United Steelworkers of America. The first union – company contract was signed in 1940.

The start of World War II in 1939 signaled the start of another boom cycle for the Sydney Steel Plant. Once more the war effort took all of the steel that the plant could produce. The Plate Mill was recommissioned and, over the length of the war, provided plate steel for the construction of ships that supplied the British Isles, allowing them to survive. By now a #2 Open Hearth shop was operating with two 200-ton tilting furnaces. In time this would expand to include 6 of these furnaces and the phasing out of the ten-50 ton furnaces.

The war years also included a tragic event for Sydney Steel. In 1942, German Submarines sank four ships that were carrying ore from Wabana to Sydney. Seventy lives, mostly Cape Bretoners, were lost. But, 1942 also included a positive event when a 10-ton electric arc furnace was introduced for the manufacture of specialty steel. This technology was basically the same as that of the electric arc furnace commissioned in 1989.

At the end of the war, Canada found itself with a large fleet of modern ships at its disposal. Rather then operate its own merchant navy, they sold them off. Dosco purchased three of these ships for $1.00 each and they served the company well for the next 18 years transporting ore and limestone from Newfoundland.

In 1947, Dosco was one of the major steel plants in North America. Union – company negotiations were carried out in Canada in a group known as the Big Three: Dosco, Algoma and Stelco. A strike occurred at Sydney and was not settled until the Sydney workers received the same pay as the other major Canadian steel industries. However, this was the last time Sydney workers negotiated along with their fellow workers in other parts of the country.

1 Blast Furnace was commissioned in 1947 and bunker C oil was now used to fire the Open Hearth furnaces instead of producer gas.

The 1940’s and 1950’s were profitable years and the plant employed an average of 5400 people. A look at the plant in 1957 reveals:

- A profitable plant with the potential of 1,000,000-ton yearly production

- 120 modern Coke Ovens with product recovery

- 3 Blast Furnaces

- Six 200-ton Open Hearths

- 700-ton metal mixer

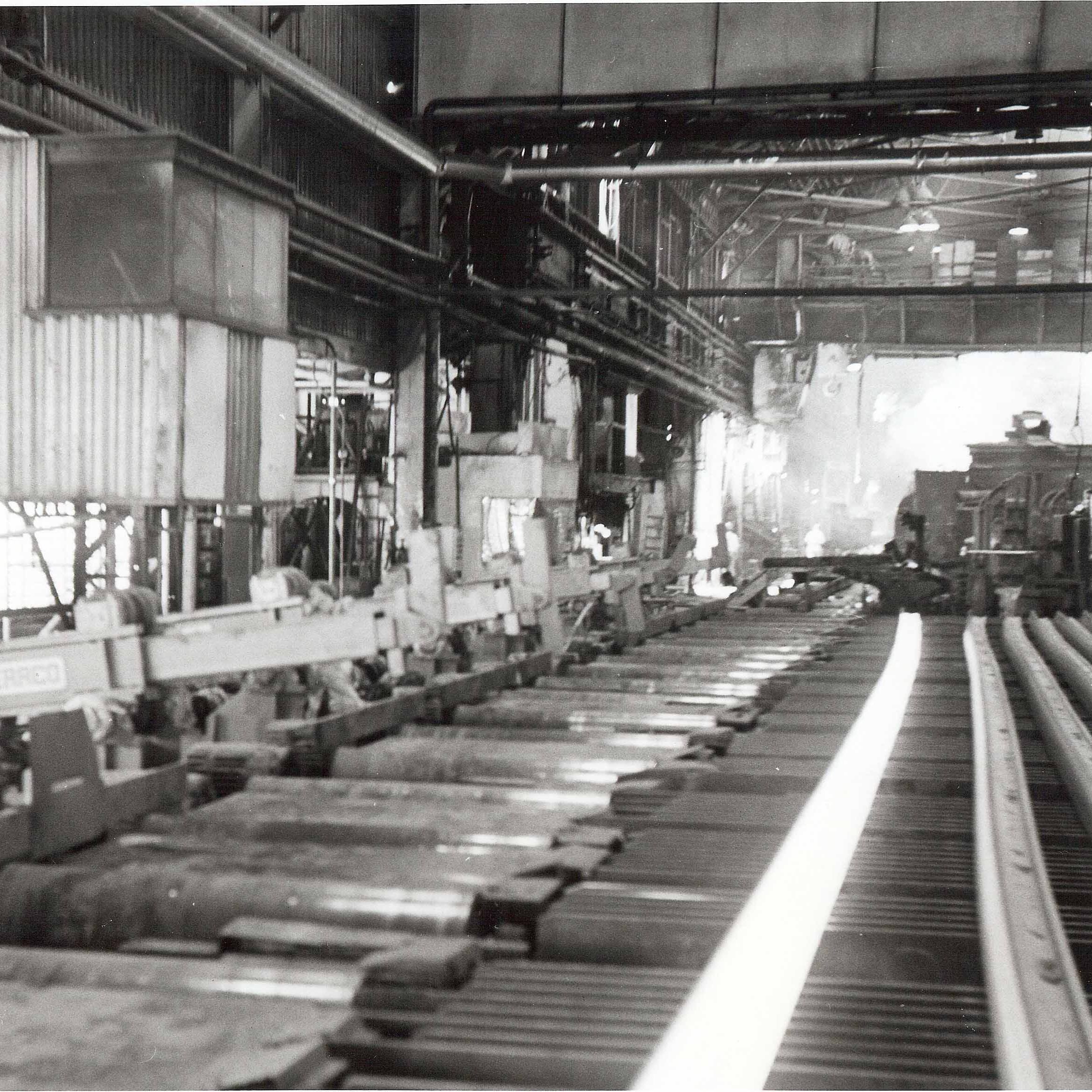

- Blooming and Billet Mill

- Rod and Bar Mill

- Wire and Nail Mill

- An important development took place in 1957. This was the construction of a coal blending and treatment plant at the Coke Ovens. Now imported coal of low sulfur content could be blended with local coal thus lowering the sulfur content of iron produced at the Blast Furnace.

The highlight, (or lowlight from today’s perspective), of 1957 was the sale of Dosco to the British conglomerate Hawker Siddeley. This company produced everything from aircrafts to refrigerators and, almost all shareholders forecast a bright future for the Sydney Steel Plant. The only dissenter was Frank Sobey who owned 20% of the shares. He said that Hawker Siddeley had a poor corporate record in Canada and, it was not in the local community’s best interest to sell to them. However, most people dismissed this as sour grapes and a case of his own self-interest over that of the community.

It soon became apparent that Hawker Siddeley was not interested in making steel, only in making money. When capital investment was needed to repair or modernize, their policy was to shut it down or sell it. Case in point was the Wire and Nail Mills. They sold the Nail Mill and closed the Wire Mill rather then spend money on them.

A few positive things did happen during the Hawker Siddeley years, however. Oxygen lancing was introduced into the Open Hearths, which reduced the time needed to produce a heat by half. Also, a very efficient stock unloader was built. The Wabana Mines were closed in 1966 and a much higher grade of iron ore was imported from Quebec. Finally, after 60 years, the steel plant had good control over the impurities from iron ore. Only 20% of the coal being used was from the Cape Breton coalfield and this was blended with low sulphur Virginia coal.

During the 1960’s the local steel industry went into another bust cycle. Hawker Siddeley’s answer to this was massive layoffs and closure of operations. By 1967 the plant was losing money. Hawker Siddeley told the Provincial Government that if they would supply the money to modernize, they would guarantee 25 more years of operation. This was met with a dim view. The Government made it quite clear that they were not in the business of financing major conglomerates.

On October 13th, 1967 (The infamous Black Friday), Hawker Siddeley dropped a bombshell on Sydney. They announced that they were closing the Sydney Plant permanently as of April, 1968. This caught not only the Provincial Government by surprise, but the whole community as well.

The community rallied together and a massive “Parade of Concern” in November convinced the Provincial Government to take over the operation of the Sydney Steel Plant and operate it as a crown corporation.

iIn January of 1968, the plant became the property of the Provincial Government of Nova Scotia and became known as the Sydney Steel Corporation, (SYSCO). In 1969 the steel industry was back in a brief boom cycle and, for the first time in history 1,000,000 tons of steel was produced. The company also paid an employee’s dividend for the only time in its history. This convinced the Government to make a capital investment in the modernization of the aging mill. 92 million dollars was invested and new equipment included a modern rail finishing Mill, which went into operation in 1973. A Continuous Caster was commissioned in 1975 as part of the modernization. It operated intermittently for six years and, although it proved to be an excellent piece of equipment, it never reached its full potential because it was not co-ordinated with a Basic Oxygen Furnace. The old tilting Open Hearth Furnaces were never able to supply it on consistent bases.

By the mid 1970’s Sysco was back in a bust cycle from which it never recovered. By now Sysco was basically only producing rails. The Billet Mill still operated but its days were numbered. Still, optimism reigned that the plant could be salvaged. A multi- million dollar two-phase modernization was begun. A new Blast Furnace was built and went into operation in 1984. It never operated at full capacity because the Open Hearths couldn’t handle the iron output.

By 1982 the plant was in dire shape financially. A misguided walkout prior to a legal strike occurred. When Sysco informed the rank and file of the blank order books, they returned to work and were then laid off for the summer. Unfortunately, 3300 workers had walked out and only 1200 ever returned.

It was now realized that Sysco would never operate economically as the large integrated plant it had been in the past. It was decided that it would become a mini-mill operation with direct reduction of scrap in an electric arc furnace. This would feed a continuous bloom caster, and thence to a reheat furnace before rolling of rail products in a universal mill. This was the second phase of the modernization period and was completed in 1989. The Coke Ovens closed in 1988, followed by the Open Hearths and Blast Furnace in 1989. In 1990 the Provincial Government wrote off the plant deficit of 786 million dollars. They announced that the modernized plant must now show a profit in order to keep operating and that a private buyer would be sought.

MinMetals of China agreed to operate the plant as a joint venture with the government in 1993, leading to their purchase of the whole operation in three years. By this time, only up to 600 employees were working spasmodically and 203 million more dollars of debt had accumulated. In 1996 MinMetals withdrew from their agreement to purchase the plant. For the next few years the government sought another buyer but, no legitimate purchaser evolved

In 1999 the Progressive Conservative party ran in the election with their main platform being the closure of Sysco. This secured the Nova Scotia mainland vote for them and led to their election. On May 22, 2000, the last rail was rolled at the Sydney Steel Plant. Not long after this the Progressive Conservative government, citing the lack of a legitimate buyer, closed the Sydney Steel Corporation.

For 100 years Sydney advertised itself as the steel capital of Eastern Canada. For all its problems, it was certainly a very positive industry for not only the community, but for its contributions during both halves of the Great War of the 20th Century. If there is one thing that can be said of the plant, it is that through good and bad times it was never dull, always interesting – an exciting time to be alive.

SOURCES:

David Erwin – Century of Steel

David Frank – Rise and Fall of Besco Reserves UCCB Library

Sydney S. Slaven – Important Years In Cape Breton Steel Beaton Institute

Sydney S. Slaven – The Dosco Fleet Beaton Institute

Sydney S. Slaven – Safety and Accidents Beaton Institute

Final Report Skills Adjustment Study Beaton Institute

Steel Project Beaton Institute

Muggah’s Creek Watershed Report Beaton Institute